"There is a certain stratum of people around the world who consider that they know what a good choice of these elements is: this is what has become known as good taste. Thus you can have what is generally considered to be good taste in pictures, good taste in gardens, good taste in interiors, and conversely you have kitsch taste, theatrical taste, vulgar taste and common taste.

"The international cognoscenti elect themselves over the generations. At the end of the nineteenth century John Ruskin made tremendous proclamations about taste which you cannot really argue with today: he was right within the context of what he was preaching. In the 1900s Edith Wharton was regarded as a paragon of taste. People like Syrie Maugham and Elsie de Wolfe were regarded as leaders of fashion and style in interior design in America, England and France in the late twenties and thirties. History has not, on the whole, proved them wrong.

"Taste is not something you are born with, nor is it anything to do with your social background. It is worth remembering that practically anyone of significance in the world of the arts, whether in the past or today, was nobody to start off with. No one has ever heard of Handel's or Gainsborough's father. Nepotism and parental influence count for little in the history of talented designers, architects, painters and musicians. Good taste is something which you can acquire: you can teach it to yourself, but you must be deeply interested. It is no way dependent upon money.

"There is in fact an acceptable way of using almost everything. If someone asked me to design a room for them, but confessed they collected gnomes, I would make a gnomescape on a table. If someone had a passion for flights of ducks I would say that I would use not one but nine flights and would arrange them in a Vasarely-type way, painting the ducks black and white alternatively."

My taste, be it good or bad, has been formed principally by an aversion to the popular or, as David Hicks describes it, vulgar and common taste – a result, I suspect, of my early years in design school and later in university where I read two magazines almost religiously and for years. The more important of the two was Design, the magazine of the now defunct Council of Industrial Design, and Graphis, a Swiss-produced graphic design magazine that was glossy, expensive and precious. There was a third, but at this remove I cannot remember the name. All I know is that it was in the pages of these magazines that I first read about Le Corbusier's chapel at Ronchamp, Moshe Safde's Habitat 67, Buckminster Fuller's geodisic dome, and many a sleek, well-designed product. It was an era of good design when the why, how and what for were paramount – an era of innovation rather than of imitation and restyling.

On my bookshelves I recently came across Phoenix at Coventry, The Building of a Cathedral by Basil Spence. I wonder if I bought it, put it away intending to read it another day and never did, until now. In my youth I once visited the new Coventry Cathedral (the 14th-century St Michael's was bombed and ruined in the Second World War) and it's clear now where my love of combining old and new comes from – for the the power of seeing that ruined stone through the huge engraved screen of window still has resonance. The combination of old and new is still at the basis of my aesthetic though the proportion of each has changed.

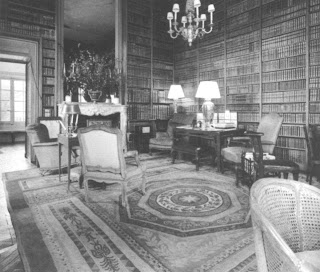

Neither ducks, flamenco dancers nor gnomes are in evidence in these two rooms – though a gnomescape might be a splendid, if impermanent, addition to the first, serene, if curiously under-lamped room. Here the combination of modern and old is exciting and, if truth be told, more reminiscent of the 1960s than the architects might care to acknowledge. The modern leavened with the old, rather than the other way round, seems balanced and fresh.

The second room is the one where one might well meet a flight or nine of ducks crossing a wall and as different a room from the first as can be. Or, so you would think – most of what is visible is modern, but what differentiates it from the first room is not only plumpness of shape, but horizon line, color, lack of emphasis on the vertical, and clutter. The eye does not rest as easily in this room as it does in the first, though the backside may well do so.

The first room is from the excellent and stimulating Shelton, Mindel & Associates: Architecture and Design, and the second from a book new to me, The World of Muriel Brandolini, my purchase of which elicited a raised eyebrow from the Celt. He was silent as he read it and made a sage comment afterwards. "Hmmm," was all he said.

Shelton Mindel's room, reminiscent of no period but its own, has a neutral, timeless quality to it, but the Brandolini room, on the other hand, reminds me no end of the late 1960s though its arch cleverness dates it to today.

I surprised myself by liking Brandolini's book for there is little that gibes with my own aesthetic. Yet, though the author veers too frequently towards kitsch there is a freewheeling quality to it all that I find appealing. Would I recommend it? I'd recommend you go to a bookstore and look through it then decide if you want it. I did.

The World of Muriel Brandolini: Interiors, Muriel Brandolini, Amy Tai, Pieter Estersohn (Photographer), Rizzoli.

In a previous post I wrote: Shelton, Mindel &Associates: Architecture and Design is one of those books I bought in a "must-have" moment and, despite it being an impulsive purchase, I remain glad I did. In the Amazon blurb above the most telling phrase to me is "luminous aesthetic" – for light enlivens every page. On the other hand, there is a faded-in-the-sun look to many of the rooms but the powerful integration of architecture, space and light cannot be denied. Not a coffee table book, but it does look splendid on a Barcelona table.

Photograph of Flamenco dancer from here.

Photograph of flying ducks from here.

Photograph of gnomes from eBay.

Pelican bookcovers from here.

Photographs of Coventry Cathedral from Wikipedia.

Poster of 2001: a space odyssey from Wikipedia.

Photograph of Aston Martin DB5 from Wikipedia.

.JPG)